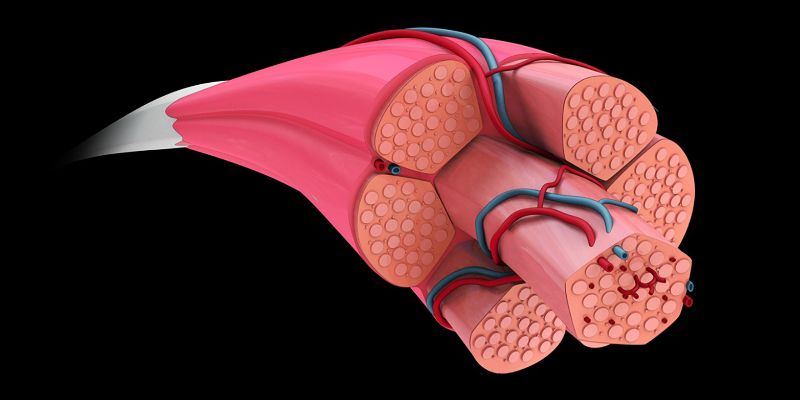

Getting oxygenated blood to exercising muscles

“In industrialised countries, the leading cause of surgeons having to amputate a foot or leg is impaired vascular supply to the muscles of diabetic patients,” Katrien De Bock says. As Professor for Exercise and Health at ETH Zurich, she and her team study how to treat vascular disorders of the muscles and how new blood vessels form. It’s common knowledge that exercise and sport stimulate the formation of blood vessels. By contrast, very little is known about the underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms. “Once we understand these mechanisms, we can work towards systematically improving the blood supply of patients’ muscles,” De Bock says.

In mice and using cultured human cells, De Bock and her colleagues have now investigated how exercise promotes the formation of thin blood capillaries in the muscle in healthy subjects. Turning the spotlight onto the cells of the vascular wall (known as endothelial cells), they discovered that there are two capillary endothelial cell types, which can be distinguished by the molecular marker ATF4. It turns out that cells with very little ATF4 are mainly found in the capillaries supplying the white muscle fibres, while cells with high levels of ATF4 primarily form part of the blood vessels close to red muscle fibres.

Ready to go

Moreover, the scientists demonstrated that exercise predominantly stimulates cell division of endothelial cells with high levels of ATF4 (those near red muscle fibres), leading to the formation of new capillaries. By contrast, exercise does not elicit a direct response in cells with very little ATF4. “Endothelial cells with high levels of ATF4 are on 'metabolic standby mode', always ready to start forming new vessels,” De Bock says. ATF4 is a regulatory protein inside the cell. Cells with this protein are primed to quickly respond to the appropriate stimulus. As soon as a person – or, in this case, a mouse – starts exercising, these cells increase their amino acid intake and accelerate the formation of DNA and proteins, encouraging rapid cell proliferation. This ultimately leads to the formation of new blood vessels.

Why these ‘ready to go’ endothelial cells are mainly found near red muscle fibres is not yet known. The researchers intend to unravel this mystery next. In addition, the scientists hope to use these findings to develop therapies that stimulate the growth of muscular blood vessels in patients suffering from diabetes or arterial occlusions and in organ transplant recipients.