Getting hydrogen out of ammonia

Without hydrogen, Kevin Turani-I-Belloto surely wouldn’t have chosen hydrogen storage as the topic for his PhD thesis, and he probably wouldn’t even have come to EPFL. But today, it’s hydrogen’s cousin ammonia – NH3, a combination of hydrogen and nitrogen – that’s keeping him busy. Turani-I-Belloto is an associate researcher at EPFL’s Catalysis for Biofuels research group headed by Prof. Oliver Kröcher, and he’s developed a catalyst that can break down ammonia at a lower cost than existing methods, and without the need for rare-earth metals. Last fall he received an Ignition grant from EPFL’s Vice Presidency for Innovation and an Enable grant from EPFL’s Technology Transfer Office to help him build a prototype. And now, he’s been selected for a Bridge Proof of Concept grant, offered through a joint initiative by the Swiss National Science Foundation and Innosuisse.

Hydrogen holds just as much promise for storing the surplus power from renewable energy as for being used as fuel. It’s the smallest molecule in the universe and can escape through even the tiniest hole. Owing to its ultra-low density, it has to be stored at a pressure of 350 or 700 bars – depending on the standard – for use in gas form, or at a temperature of –252°C for use in liquid form. Distribution networks for hydrogen remain scarce and, therefore, expensive. Operators of ships and aircraft – vehicles for which electric batteries are not yet viable – are placing their bets on hydrogen or synthetic fuels made from hydrogen, although the production of these compounds isn’t very energy efficient.

A secret formula

That’s where Turani-I-Belloto’s new method comes in. He proposes using ammonia to transport hydrogen. “Today, half of the hydrogen that’s produced goes to the manufacture of ammonia, which in turn is used as the main ingredient in fertilizer,” he says. Ammonia is a colorless gas but not odorless, meaning leaks can be detected fairly easily. It can be liquified at a relatively low pressure (8.5 bars) and a reasonable temperature (–33°C), making it a good candidate for transport. Liquid ammonia also has a higher energy density than liquid hydrogen. “What’s more, distribution networks for ammonia are already well-developed around the world,” says Turani-I-Belloto. “Hence my idea for using it to transport hydrogen.”

“What I want to do is leverage the benefits of each gas: ammonia for transport and hydrogen for energy, producing it from ammonia right where it’s needed” says Turani-I-Belloto. “That’ll make it possible to meet demand for clean energy, both for cargo vehicles and in an array of other industries.” Turning ammonia into hydrogen requires the use of a catalyst. “Catalyzing agents do exist, but they’re either not effective enough or they’re too expensive, like ruthenium, an extremely rare metal. My system delivers high yields, uses abundant raw materials and cuts the catalyst cost by a factor of over 200.”

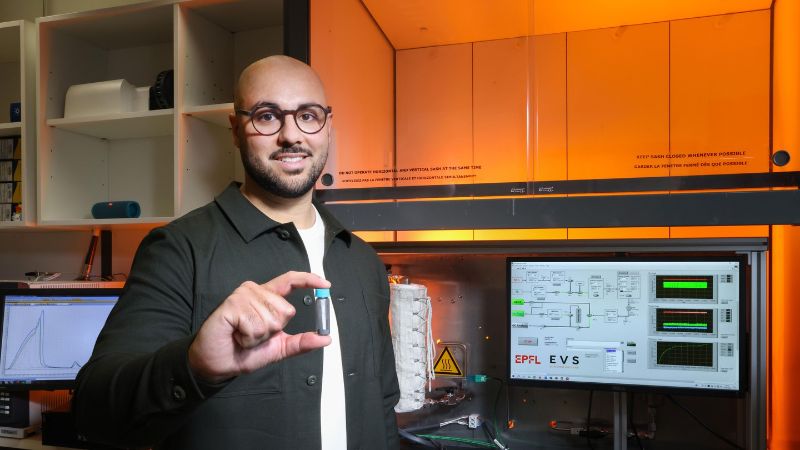

Funding agencies clearly see potential in Turani-I-Belloto’s technology, although he’s keeping the details of his process under wraps. “It’s my magic formula,” he says. So we won’t get a peek into the black box. However, his compact demonstrator is now set up in the research group’s laboratory, and it has demonstrated the potential of his innovative catalyst. He’s filed for a patent for his invention.

“If we’re successful in using ammonia to store hydrogen, that will unlock an entire value chain,” says Turani-I-Belloto, who’s working tirelessly to reach that goal.