Climate change and nutrient fluctuations disrupt networks in lakes

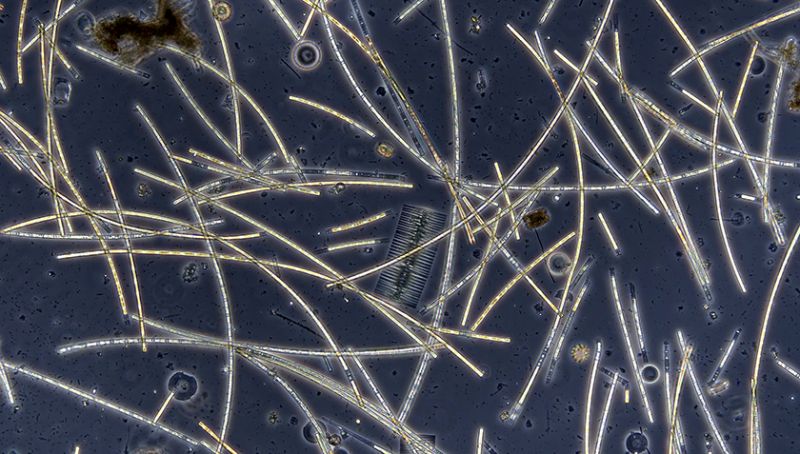

In most lakes, there are millions of small creatures that generally remain hidden from our eyes. What they have in common is that they are suspended in water and move with the current. That is why, altogether, they are called plankton, which in Greek means “the one that wanders around.” Not only is there an incredible diversity of sizes and shapes among the plankton, but also of ways of life.

Relationships provide stability

Plant plankton (phytoplankton), which include green algae and diatoms, use the sun as an energy source and produce the substances they need to grow with the help of sunlight, CO2 and water. These primary producers form the basis of food webs in water bodies. The first to benefit from them are the animal plankton (zooplankton), which includes, for example, small rotifers and ciliates or water fleas that graze on algae. These creatures, in turn, provide the food base for predatory zooplankton species – which are subsequently eaten by larger predators such as fish.

But the interplay is not limited to eating and being eaten. Species also interact with each other, for example, by competing for sources of food or when they can thrive better under the protection of another species. All of these multiple interactions not only regulate the food web, but also provide stability to the entire aquatic ecosystem.

Warming reduces degree of connection

In spite of the great importance of this highly complex plankton network, little research has been done on how it responds to two of the most important anthropogenic threats – climate change and nutrient inputs caused by over-fertilisation. We know that higher water temperatures and changing phosphate concentrations affect the abundance and diversity of plankton communities in our lakes. However, it is still largely unknown how this affects interactions between species.

The aquatic research institute Eawag has now succeeded for the first time in providing substantiated statements on this subject. The results were recently published in the journal Nature Climate Change. Ewa Merz, ecologist and first author of the study, summarises: “We have found that the warming of lakes, as we have observed in recent decades, reduces interactions in the plankton network. There are fewer interactions and they are weaker. This decline is particularly pronounced when lakes simultaneously have high phosphate levels.” If the nutrient content in a body of water like Lake Zurich increases even slightly, this could already have dramatic consequences for the entire network in a warming world and destabilise the ecosystem. According to Merz, this could threaten not only a loss of species, but also a decline in ecosystem services – such as lower water quality due to increasing cyanobacterial blooms or a decline in fish populations due to changes in the food web.

Unique data set thanks to the diligence of the Cantons

This study was made possible by a data set that is probably unique of its kind. Merz had at her disposal plankton samples from ten Swiss pre-alpine lakes, as well as measured values for water temperature and phosphate levels, which the Cantons collected monthly between 1977 and 2020 and made available to Eawag. With an innovative data analysis carried out at the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS), Ewa Merz succeeded in reconstructing entire ecological plankton networks and determining their relationship to phosphate levels and water temperature.

Including plankton in monitoring programmes

The study could mean double added value for the Cantons. “On the one hand, it is gratifying for them to see that the data they have carefully collected over so many years is being used. On the other hand, they are also interested in the results,” says Merz and emphasises the very good collaboration with the authorities.

The study also provides concrete recommendations for practical applications: “To prevent the food webs in the lakes from deteriorating even further, we would need to mitigate global warming on the one hand and strictly control nutrient inputs on the other. If we continuously monitor plankton communities, we can better anticipate major changes in the ecosystem. Our study shows that small grazers such as ciliates or rotifers are important indicators of such changes. Accordingly, they should be sampled in future lake monitoring programmes.”