Everything is interconnected – many losses are irreversible

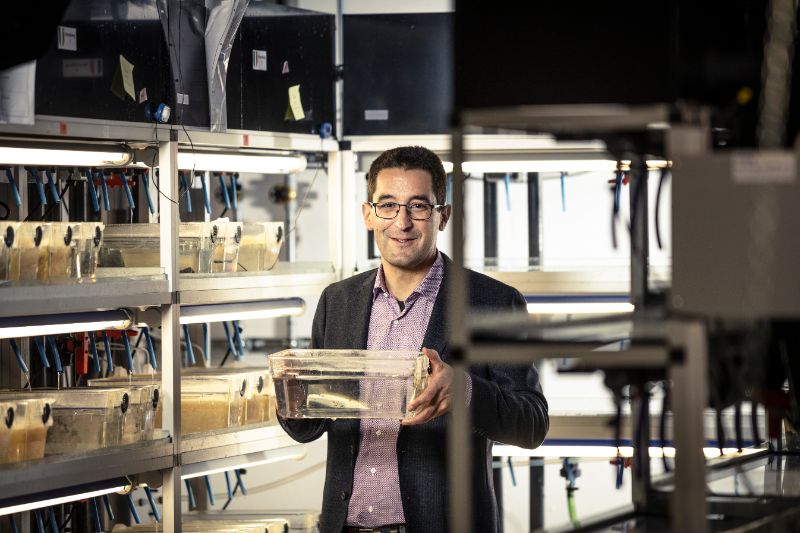

What Florian Altermatt, Professor of Aquatic Ecology at the University of Zurich and Group Leader in the Department of Aquatic Ecology at Eawag, has to report is alarming: “The loss of biodiversity has assumed dramatic proportions,” the scientist states, “there has been a 50 to 90% decline in some populations worldwide, especially in aquatic habitats. Around a million species are at risk of extinction.” The human made change in biodiversity on the Blue Planet is now called mass extinction, similar to that of the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago. The extinction of species is irreversible, and the changes in biodiversity are mainly due to changes in land use, climate change, pollution of ecosystems, direct persecution of populations or even invasive species. “Scientists have been aware of all of the above for decades,” said Professor Altermatt, “humanity presumably only has a small window of two to three decades to reverse this development.”

Since the 1980s, scientific biodiversity research has intensified and, over time, also turned to more socially relevant issues. Originally, this came from taxonomic research, in which biodiversity was classified according to certain criteria, and from ecology, in which the functional significance of biodiversity or also interactions of species were scientifically investigated. At the same time, it became increasingly apparent that biodiversity and species composition are negatively affected by human-made environmental changes. All of the above led to the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992. “This was a formative moment that brought the issue of biodiversity to the attention of people outside the scientific community,” said Professor Altermatt.

Eawag covers a wide range of scales in biodiversity research in various areas. In this way, pivotal, fundamental questions can be researched: How does biodiversity occur? How can it be preserved? How does biodiversity affect ecological processes? This occurs, for example, at the level of bacteria in waste water treatment plants. Or at the level of natural ecosystems: How does a change in the algae communities in lakes affect the biodiversity of invertebrates or fish? “At Eawag, biodiversity research is covered across the whole range of aquatic ecosystems,” is how Professor Altermatt sums it up. In this way, complex trophic cascade effects can be researched which arise when food chains change at different levels. The entire interdisciplinary research community at Eawag is often involved in this across the most varied of disciplines, ranging from the engineer to the social scientist and field ecologist. The research approach usually adopted at the institution is now similarly sophisticated. The same issues are theoretically studied and mathematically modelled, investigated in parallel using experiments under controlled conditions in the laboratory and researched in small model ecosystems, before later being transferred to the entire landscape. Basically, this is the formula for reducing complexity and getting application-oriented results.

The latest strategic Blue-Green Biodiversity Research Initiative (BGB) for interdisciplinary research on “blue-green”, aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity, which is supported together with the WSL, is also to be seen in this context. In the autumn of 2017, the Federal Council adopted an action plan on the biodiversity strategy, the aim of which is to develop biodiversity through ecological infrastructure and species conservation, among other things. The ETH Board has now taken the ball and is running with it by supporting the BGB initiative, which is planned for five years until 2024, with CHF 6.5m. Under the co-leadership of Eawag researcher Altermatt and WSL scientist Catherine Graham, Group Leader in Spatial Evolutionary Ecology and Associate Professor of Ecology and Evolution at Stony Brook University (USA), synergies are created, in order to strengthen the internationally recognised environmental research of the two research institutions with the aim of researching biodiversity at the interface of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

Annual Report 2020

This article was prepared as part of the ETH Board's Annual Report 2020 on the ETH Domain.